Vintage Furs... Made in Bellingham!

Reader discretion is advised: the writing of this blog post was enabled by the killing of many small animals nearly 100 years ago.

I am not a fan of the fur industry or the slaughtering of small animals. I am however, a history nerd and thrift-store enthusiast. I was intrigued when Good Time Girl guide Jane found this locally-made vintage fur coat at textile reuse center Ragfinery.

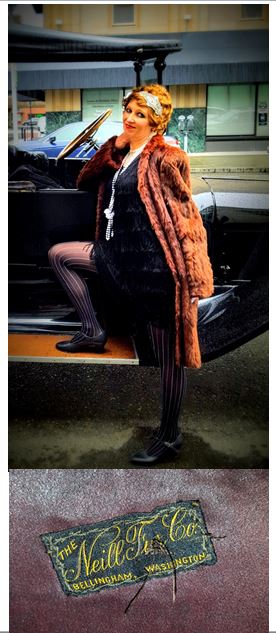

Above: The author modeling the fur coat. Below: Hand-sewn coat label

The coat is a little worn and smells like great-aunt-Edna’s closet, but has been a useful costume addition as well as a conversation piece. The tag inside reads “The Neill Fur Co, Bellingham, Washington." I wanted to know more of the back story of the coat as a local historic artifact.

Vintage fashion is not my particular area of expertise, but after poking around online looking at a lot of vintage furs, my best guess is that the coat dates from the late 1930s or early 1940s, and is perhaps made from squirrel or muskrat. These were both less expensive options in terms of fur, and with its no-frills style, this coat may have been more “affordable” in its day.

In the 1920s raccoon coats were all the rage - they would keep you warm while driving in a Model-T and watching football games. Fur markets reached a peak in North America in the 1920s and 1930s, declining during the depression, and continued on a downward spiral in the early 40s due to the war effort and material shortages.

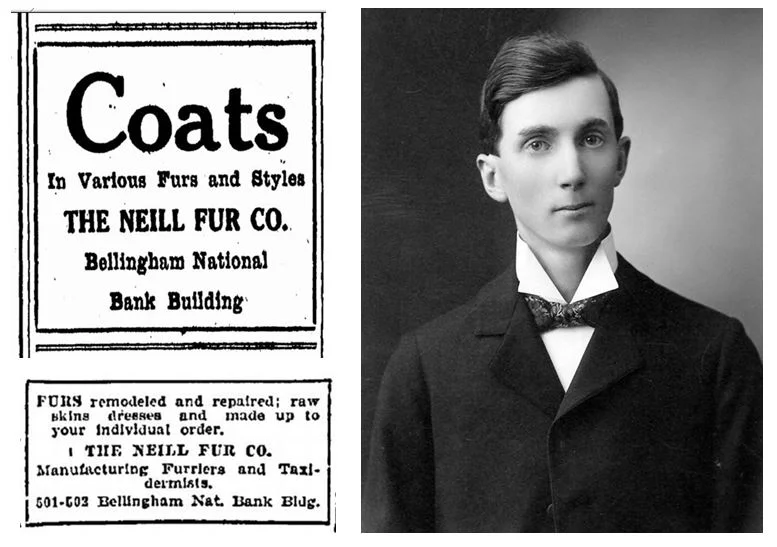

The Neill Fur Company ran small and straightforward ads in the Bellingham Herald during the 1920s. The company advertised “coats in various styles," and “furs remodeled and repaired,” as well as “raw skins dressed and made up to your individual order." That’s right - bring us your squirrels, folks!

Neill Fur Ads from the Bellingham Herald, circa 1920. Photo of Walter Neill courtesy Gary Gordon.

Proprietor Walter L. Neill had come to Washington with his family as a young man. In 1910 Walter Neill’s sister “Birdie” had married Dr. Samuel Torney, a Canadian born ear-nose-and-throat physician. Dr. Torney had been practicing in Bellingham since 1905 in the Red Front Building at Commercial and Holly. The Torneys bought a house at 521 17th Street, and Walter Neill moved in with them.

Walter Neill started his fur and taxidermy business in Bellingham around 1920, first operating from the Bellingham National Bank building at Cornwall and Holly Streets, and then moving to the Kirkpatrick Building at 1409 Commercial Street, where he operated between 1930 and 1948.

Walter married Louisa Dunlop in 1924, and the couple moved into house across the street from the Torneys, at 601 17th Street. After Dr. Torney’s death in 1927, Walter and Louise Neill moved in with Birdie.

Photo of Birdie Neill Torney modeling a lovely fur coat (dog's name unknown). Courtesy Gary Gordon.

Bellingham had a variety of furriers to choose from over the years. David Horowitz was a furrier who in 1907 advertised himself as “The Russian Furrier.” After World War I began he changed his name to the “American Furrier.” Horowitz passed away in 1920, around the time when Walter Neill and his main competitor, John Slaninka, were just getting started.

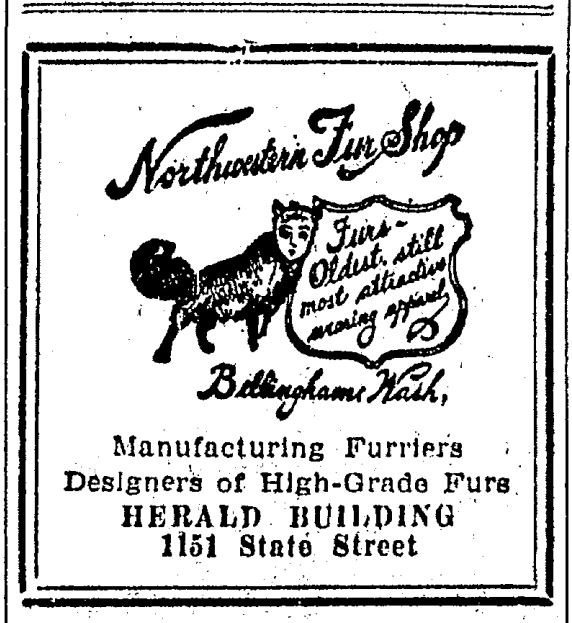

Hungarian immigrant John Slaninka arrived in Bellingham in the early 1920s and opened the Northwestern Fur Shop in the Herald Building on State Street. Slaninka’s Northwestern Fur Company had a creepy little logo of a critter with a human face

Northwestern Fur Shop Ad - Bellingham Herald 1930

Furriers such as Walter Neill and John Slaninka made their coats on site, by hand, and each was a one-of-a-kind garment. Furriers were often also “taxidermists” who knew how to tan their own furs from whatever critters they could get their hands on. They could also buy wholesale furs from the” Friese Hide & Fur Company” owned by August J. Friese. The Friese plant on Bay Street also rendered animal fat and was the source of odor complaints in the 1940s. Cured furs were fashioned into coats and capes and other garments to which the furriers would sew in their own labels. They also provided fur storage and care, cleaning and “remodeling.”

Local stores such as Wahl’s and Newton’s also sold fur coats, and advertised annual “fall fur sales.” Bellingham stores in the 1920s and 1930s mainly advertised more affordable furs such as Seal, Skunk, Squirrel, Muskrat and Marmot. The most expensive furs were sable, ermine, mink and fox.

Using creative marketing, the fur trade tried to make less glamorous furs sound more desirable. Furs were altered and advertised as being from false and sometimes fictitious species such as “Baltic black fox” which was actually rabbit. “Hudson Seal” was actually was sheared and dyed muskrat. The U.S. Federal Trade Commission eventually stepped in and after 1938 transparency was required. Furriers began to use terminology such as “mink-dyed-muskrat” and “sable-dyed-squirrel.”

Prices in these ads ranged from $77 for a Muskrat coat, around $1000 in today’s money, to $845, for a mink, almost $12,000 today. So… even the “cheap” Muskrat coats would have been out of the budget of many!

In the fall of 1930, the Herald’s “Shopping with Sally” section featured John Slaninka’s take on the new fur styles and options for the season:

“Muskrat coats will still be the most popular... The very lightest muskrat coat is made of the strips of fine fur coming from the underside of the little animal. This is called silver muskrat. The golden muskrat’s fur comes from the sides of the animal and the dark brown muskrat coat is made of the back strips of skins. Still another muskrat coat is made of skins which have been bleached and dyed buff.”

Numbers vary between sources, but it apparently takes about 30 muskrats and 60-100 squirrels to make one coat, depending on the design and dimensions.

1940 Bellingham Herald ad - "Sable-Dyed Muskrat"

Luckily for the animals involved, the popularity of fur in fashion has plummeted in the past 50 years or so. In the 1950s the cost of manufacturing coats exceeded the cost of the raw materials. In the public imagination, fur coats were associated with the idea of a “kept woman” whose dependency did not carry over well into the more liberated 1960s. By the 1970s and 80s groups such as the Animal Liberation Front and PETA helped drive down demand even further in bringing animal suffering and ethical concerns to public awareness. Many fur coats from the former glory days have ended up in grandma’s attics and second-hand stores.

L: Gary Gordon with his great-aunt Birdie in the 1950s. R: Walter and Louisa Neill in their later years, Seattle, WA. Photos courtesy Gary Gordon.

The Neill Fur Company was no longer listed in directories after 1950, when Walter Neill retired and moved to Seattle. Neither Walter and Louise Neill nor the Torneys ever had children. Birdie Neill Torney “adopted” her great-nephew Gary Gordon as her surrogate grandson. Gary was kind enough to share these family photos with me. Walter Neill passed away in 1968 in Seattle.

(For more info on the history of furs in fashion see: http://www.fashionintime.org/furs-fashion-early-twentieth-century/)