A Cold and Stormy Night October 1888

Ella Rhoads Higginson’s recollection of the “horrors” she encountered on her arrival on the shores of Bellingham Bay on a dark night in October of 1888 is a great seasonal read for Bellinghistory nerds. The story was written some 20 years after the fact and originally published in the American Reveille June 14, 1908. It was later reprinted in Edith Beebe Carhart’s 1926 compilation “A History of Bellingham, Washington” and in Lela Jackson Edson’s 1951 “The Fourth Corner.”

Ella Rhoads Higginson was born in Kansas and moved to Oregon with her parents as a very small child. She married Russell C. Higginson in 1885 in Portland, and they began their journey to Whatcom a few years later, having heard of the town’s latest “boom.” Those of you who have been on our tours and/or know a little about our local history can especially appreciate the picture she paints of what it was like for a “lady,” even one who grew up in Oregon Territory, to arrive on our shores in the 1880s.

My First Voyage to Bellingham

By Ella Higginson

It was a cold and stormy night in October, 1888, that we boarded the old Idaho – even the rheumatic and short of breath – bound for Sehome and Whatcom. A handful of lights flickered on the hills where now is one of the marvels of the country – Seattle.

Seattle claimed only 20,000 people in 1888; and neither Seattle nor Bellingham was ever known to claim less than it deserved.

There were two people on the Idaho that night whom I shall never forget. One was a girl from La Conner; the other was a deckhand. From the latter I received the first genuine, spontaneous kindness that cheered my heart on Puget Sound.

We had brought all the way from Eastern Oregon a big, black curly dog, named Jeff, who was precious. He was chained on the lower deck directly under our cabin, and his sobs and moans of loneliness made sleep impossible for me. I could hear the deckhands swearing and throwing things at him; but now and then a kind, sweet tenor voice consoled and comforted him.

But the sobs and moans continued. At two o’clock in the morning, I arose, dressed, and went down to the lower deck. The deck hands were all lying around on the floor sleeping. I was compelled to walk between them, around them, and almost over them to get to the dog. Finally one sat up.

“Can I do anything for you, lady?” said he; and it was the kind tenor voice that spoke – low not to arouse the other men.

I asked him if I might not stay down there with my dog.

“It wouldn’t be just the thing,” said he, politely. “But I’ll tell you what. You kind of introduce me to your dog, and I’ll lay down by him and pet him now and then.”

So I told Jeff that this man, whose face I could not see in the darkness, was a friend who would take care of him; and there was no further sound of grief from the dog that night.

I never saw the man and I never heard his voice again; but he is unforgotten. He belonged to the great Order of Kind Hearts, whose members may be found the world over, in high places and low.

The girl from La Conner I remember for another reason. We had read the most brilliant stories of Whatcom’s ‘booming’ prosperity, and our hopes were high. I sat on deck talking to the girl.

“Whatcom is having a boom, isn’t it?” said I, innocently. I used the word almost with awe, not knowing exactly what it meant, being from Oregon.

“Yes,” said the girl, yawning. “Whatcom is always having ‘booms’.” The words gave me a quick shock of apprehension, and in the years that followed they became a kind of household motto.

We left Seattle at eight o’clock on a Tuesday night and we did not reach Whatcom until midnight Wednesday. Where we were in the meantime I neither know nor care; but like the Wandering Jew, we ‘kept going’ all the time.

It was raining, and the light of the night was black. We landed at the old Colony wharf, nearly a mile out over the tide-flats. There was one man on the wharf, with a smoky lantern and a wheel-barrow, in which to carry the mail. “You’d better follow this lantern pretty close,” said he, cheerfully. “There’s some pretty terrible holes in this wharf. If you happen to step in one, you’re a goner from Gonerville, sure.”

We were exhausted with a long journey and loss of sleep; and our hearts were low as we went stumbling along behind that smoky lantern, expecting with every step to go plunging to the bottom of the bay.

At Thirteenth and C streets the wheelbarrow and the lantern stopped and we were left in inky darkness.

“There’s two good hotels,” a man told us. “One’s over on Fourteenth; the other’s the nearest. It’s straight up Thirteenth about two blocks. You’ll have to walk careful. They’re just raising the grade. Some’s raised and some ain’t and you’re liable to pitch down fifty feet onto the tide flats or into the bay. You’d best put down your umberell and jab along ahead of you with it.”

As we started out on our dismal procession, he called after us: “Say, lady! Hold up your dress! It’s soft oozy mud clean to your knees that you’ve got to wade through.”

There were no sidewalks; nothing but soft mud. We toiled painfully and silently through it. We could not see one another, we could not see the earth, nor the heavens. But at last we did see the ‘hotel,’ and when we had fully seen it, we turned about and retraced our steps, in search of the other ‘good’ one. The one to which we had ‘jabbed’ our way with our ‘umberell’ was a low saloon with three or four rooms above it. The saloon was full of men smoking, drinking, gambling and clog-dancing. One ‘fiddle’ squeaked out a pitiful discord, the player beating time with his foot.

At two o’clock in the morning we reached the ‘other.’ There was a saloon on one side of the hall, and a parlor on the other side. Mud dripped and oozed from our clothing and from the tip of every hair on the dog.

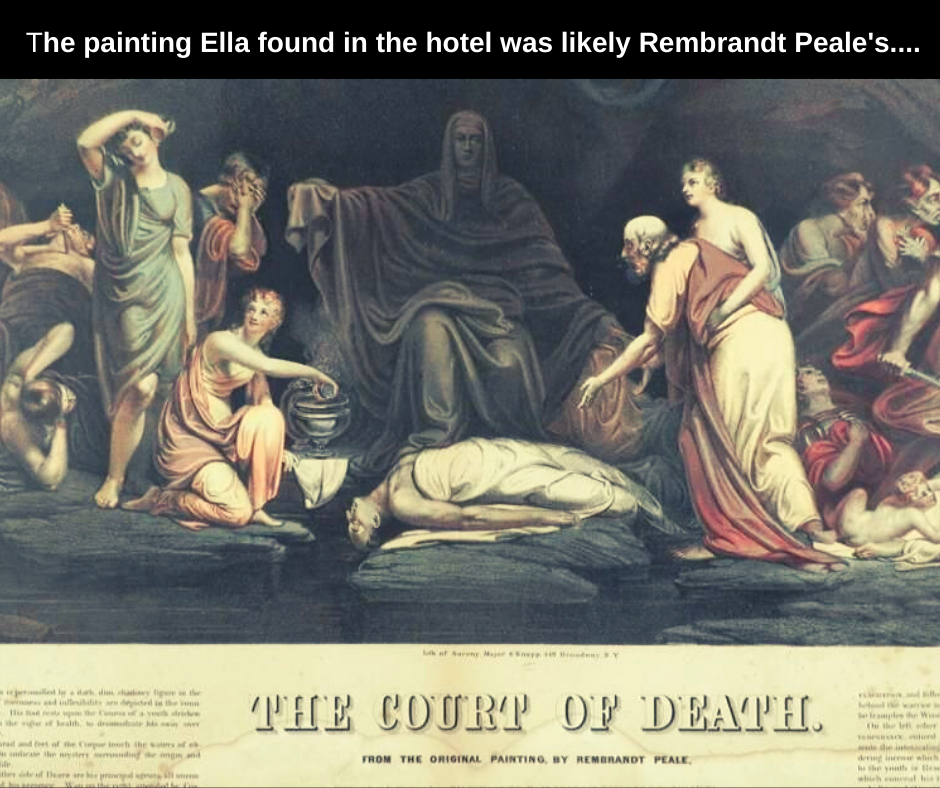

While negotiations for rooms were in progress in the saloon, I sat on the edge of a red plush chair in the parlor. Seeking for consolation in my extremity, I lifted my eyes to the pictures on the wall; and there, facing me and filling a black frame at least six feet square, was The Court of Death. My feelings at that moment will be appreciated by those who know the picture; and to those who do not, it is useless to attempt to describe them.

“This,” I said to myself, not knowing was yet to come, “is the last straw” – and I shed my first tears on Puget Sound.

We were assigned the chamber of honor over the saloon; and scarcely had we fallen asleep when we were awakened by the most terrifying and blood-curdling sounds beneath us. Oaths, scuffles, groans of mortal agony, and pitiful calls for help, stupefied us with horror.

There was no key to our door and I had fortified it with a chair under the knob. I now arose and wheeled the bureau up against the chair; and if I could have budged the bed, I should have had it against the bureau, notwithstanding the scorn of the other occupant of the room.

In the morning we learned that a man had really been stabbed to death, and that it was his dying groans we had heard. Desperate, then, became our search for a place to live, and in our daily increasing anguish of body and mind, we even nerved ourselves to approach private residences and ask for rooms. Had it not been for the kindness of the late Mr. H.E. Waity, we could not have remained on the bay.

We settled down to live, at last in Sehome, which at that time consisted of Morse’s hardware store, Carter’s dry goods store, an eating house where one could do everything on earth save eat, a drug store, a livery stable, one cow – with her milk all engaged, yea to the last drop – a saloon for every ten men, and mud.

Between Sehome and Whatcom was solid forest. A wagon road wound between, but it was impassable, so we went to town on the beach – when the tide was out. When the tide was not out, we stayed at home.

There were no sidewalks in Sehome, and women waded about in rubber boots. But ah, the joy of those first years! All was “boom,” rush and excitement. Each day was better than the one that went before. Fortunes were made over night on corner lots and every frog on Sehome hill said, “Struck it – struck it!”

All old cities have names for different sections and it has long been one of my fondest hopes that the time would come when we of Bellingham would think enough of our town, of one another and of ourselves, to forget all personal feeling on the matter of names and revive the old ones to designate locally certain districts. Fairhaven, Whatcom, Sehome – these names are dear to our hearts, and I have never been able to understand why we should not retain them, just among ourselves, not as official names, but as names of affection; just as one keeps placing the little chair at the table after its little owner has gone away. When asked in what part of Bellingham I live, I should like to reply, “In Sehome” – without offense to any one.

At the end of her story Ella is referring to the ongoing arguments over names as the various towns along the bay grew together. Even after finally consolidating as “Bellingham,” in 1903-4, tensions and rivalries remained between folks from “Fairhaven,” “Sehome,” and “Whatcom.” The name of Bellingham was chosen at consolidation for being the most neutral, being the name of the bay and a small settlement that had never been much and merged with Fairhaven. One down-voted suggestion was the awesome mash-up “What-Haven.” At any rate, the names were still a contentious issue in 1908 when she wrote the piece. Now we do have neighborhoods, schools and more bearing the names of Sehome, Whatcom and Fairhaven - the latter having always managed to maintain a strong identity.

Though Bellingham has come a long way from the rowdy saloons on the mudflats of Bellingham Bay in 1888, most of us have had a few miserable travel experiences and can relate a little to Ella and her husband’s trials. The hotel they spent the night in is known to have been the Whatcom House at the corner of Astor (14th) and E Streets, run for many years by the John R. Jenkins family. The first hotel they opted not to stay in might have been the the Chicago House, built for J.P. DeMattos who later became mayor in circa 1886. (See the photo gallery below for images) or perhaps it was Jacob Beck’s “Pacific House” which also served as the towns first brewery. At any rate, most “hotels” at the time were little more than some rooms over a saloon.

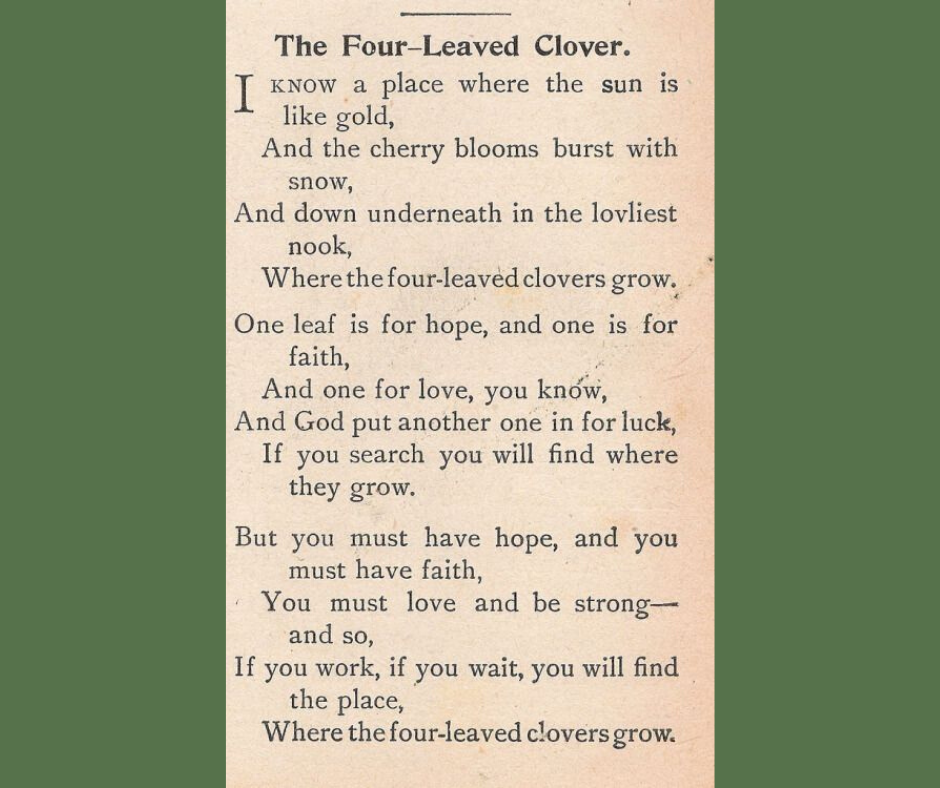

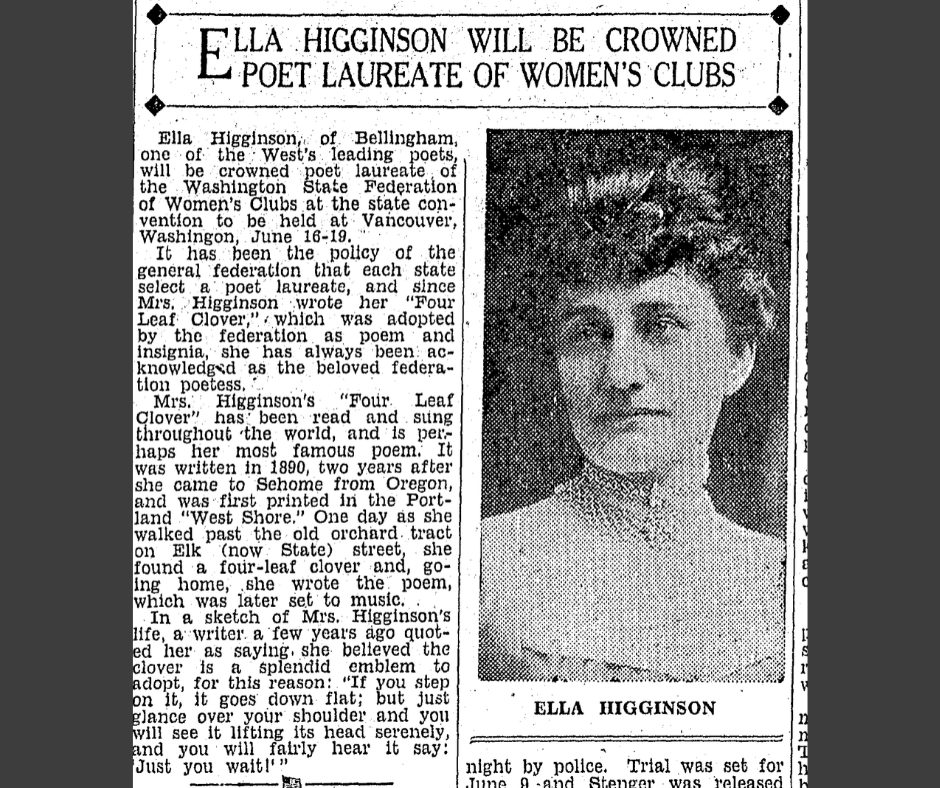

The Higginsons settled in Sehome, where Russell operated a drug store on “Elk Street” (now State). Ella Higginson began her writing career, publishing short stories and poems, most set in or inspired by the Pacific Northwest. Ella was awarded title Poet Laureate of Washington in 1931, and passed away at her home in December of 1940. The Higginson’s beautiful house on Sehome hill was torn down in the 1960s to make room for WWU’s Mathes and Nash Halls. “Higginson Hall” was named in honor of them.

Ella Higginson became largely forgotten over time, until recently thanks to Laura Laffrado of WWU who is responsible for the revival and republishing of Ella’s work and legacy, complete with the installation of a bronze bust of Ella at Wilson Library at WWU in November of last year.

Check out our photo gallery of related images and links to more things “Ella Higginson” below.